8% off orders over $100, 15% off orders over $150, 20% off orders over $300.

Menu

-

- Specials

-

Types

-

Symbols

- Auspicious Cloud | Heaven

- Lotus | Purity & Elevation

- Phoenix | Rebirth and Fidelity

- The Nine | Eternity and Completeness

- Bamboo | Strength and Resilience

- Ruyi | Wish Fulfillment

- Moon | Mystery & Elegance

- Herbal Locket | Hidden Protection

- Tassel | Elegant Charm

- Butterfly and Flower | Love

- Plum Blossom | Endurance and Resilience

- Chinese Knot | Harmony, Tradition, Legacy

- Pumpkin | Prosperity & Abundance

- Pipa | Celestial Music

- Hulu Gourd | Protection and Prosperity

- Fish | Prosperity

-

Collections

- Atlantis

- Revive Your Inner Kingdom

- Auspicious Origin

- Auspicious Flower

- Udumbara Flower

- Return to Origin

- Celestial Cloud

- Elf Forest

- Gold Lotus

- Serene Lotus

- Pearl Elegance

- Radiance

- Metropolis Hermit

- The Nine

- Moon Goddess

- Tassel Elegance

- Chic Velvet Choker

- The Cloud

- Lotus Leaf

- Realm of Peace

- Four Season

-

Craftsmanship

-

Gemstones

- Pearl | Purity and Wisdom

- Jade | Stone of Heaven

- Turquoise | Protection and Healing

- Tridacna | Realm of Peace

- Lapis | Truth and Enlightenment

- Rose Quartz|Love, Healing, Compassion

- Amethyst | Clarity and Tranquility

- Amber | Vitality and Protection

- Carnelian | Courage and Vitality

- Coral | Protection and Prosperity

- Tourmaline | Energy and Balance

- Crystal | Healing and Clarity

-

Birthstone

-

Style

-

Price

-

- Jewelry Set

- Necklaces

- Earrings

- Bracelets

- Hair Jewelry

- Glasses Chains

- Rings

- Anklets

- Ornaments

- Login

-

English

8% off orders over $100, 15% off orders over $150, 20% off orders over $300.

Chinese Jade (Part 1) : Its Folklore and Cultural Significance

March 15, 2016 3 min read 1 Comment

Jade is such an notable part of Chinese culture that decades of study won’t uncover everything it has to offer to the fields of art, literature, and anthropology. While it is impossible to cover all that ground on the Divine Land Gemstone Compendium, we will give it its due weight with three articles instead of one.

Part 2 takes us into a jade workshop; Part 3 explores the symbolism that have historically appeared on Chinese jades. Before all that, though, we need to understand why jade is so highly regarded by the Chinese.

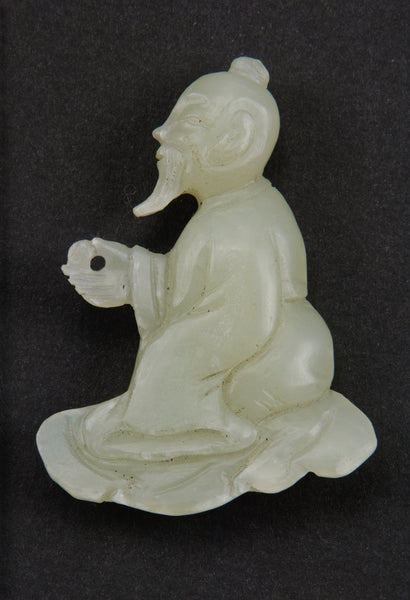

The culture surrounding jade grew up alongside that of the Chinese people. Craftsmen of China’s Neolithic cultures had already begun working in jade. They produced numerous elegant and simple ritual objects like discs and axes, which we know were precious to their users because they were buried with hundreds of these artifacts. So what makes jade important enough to take to the grave?

To begin with, jade is associated with Huang Di, the exalted original ruler of China; the originator of Chinese culture. Among his many legendary acts, he planted, grew, and harvested jade, and ate the sweet cream of milky white jade daily. Pervading Chinese mythology are many related stories of celestial mountains where jade trees grow, adding to its allure as a stone that promoted immortality.

![A jade burial suit at the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum. The Chinese used to bury the deceased in jade armor in the hopes of keeping the body from decaying. It doesn’t. (By Daderot (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons)](http://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0418/3521/files/Burial_suit__Chinese__Han_Dynasty__206_BC_-_220_AD__jade_and_replaced_copper_wire_-_George_Walter_Vincent_Smith_Art_Museum_-_DSC03669_grande.JPG?13856811042056621653)

Chinese people take jade as the essence of the energy of heaven and earth. Jade objects of different shapes were used as media of communication between humans and gods. (More on this in Part 3.) Thus, jade’s role in worship and access to the spirit world makes it indispensable in life and in death.

The Stone of Virtue

As Chinese civilization entered its first cultural flowering in the Spring and Autumn period, Confucius arrived on the scene. Among his many writings on morality and good governance is a famous mention of jade:

“Wise men have seen in jade all the different virtues. It is soft, smooth and shining, like kindness; it is hard, fine and strong, like intelligence; it's edges seem sharp, but do not cut, like justice; it hangs down to the ground, like humility; when struck, it gives a clear, ringing sound, like music; the stains in it, which are not hidden and which add to its beauty, are like truthfulness; its brightness is like heaven, while its firm substance, born of the mountains and waters, is like the earth."

With the years, these qualities would be referenced again and again. People use jade to compare with their most precious things especially the things that has inner beauty or virtue. Jade entered folk sayings as an analogy for all things admirable, —virtuous people are noble like jade; a good idea is bright like jade; a conscience is spotless like jade; edible delicacies are apparently as covetable as jade… the list goes on. To get the full color of how Chinese people speak of jade, we would have to study history and literature.

In summary, all these connotations have been passed down through the ages. Every time a mother hangs a jade pendant on her child’s neck, she communicates her hopes that he’ll grow up straight and true. When a daughter receives a jade bangle, she understands the message of protection and love that comes with it. And when a man gives a woman a piece of jade, she'll know that he cherishes her virtue as much as her beauty.

Next time you see a piece of jade, perhaps you’ll look at it differently too.

This article is part of the Divine Land Gemstone Compendium, a weekly series by Yun Boutique exploring the gemstones of ancient China and their significance to Chinese culture. See the full series here. Subscribe to the email newsletter to receive future installments.

Produced and edited by Christine Lin. Researched by Ariel Tian.

1 Response

Leave a comment

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …

James

March 15, 2016

Awesome!