8% off orders over $100, 15% off orders over $150, 20% off orders over $300.

Menu

-

- Specials

-

Types

-

Symbols

- Auspicious Cloud | Heaven

- Lotus | Purity & Elevation

- Phoenix | Rebirth and Fidelity

- The Nine | Eternity and Completeness

- Bamboo | Strength and Resilience

- Ruyi | Wish Fulfillment

- Moon | Mystery & Elegance

- Herbal Locket | Hidden Protection

- Tassel | Elegant Charm

- Butterfly and Flower | Love

- Plum Blossom | Endurance and Resilience

- Chinese Knot | Harmony, Tradition, Legacy

- Pumpkin | Prosperity & Abundance

- Pipa | Celestial Music

- Hulu Gourd | Protection and Prosperity

- Fish | Prosperity

-

Collections

- Atlantis

- Revive Your Inner Kingdom

- Auspicious Origin

- Auspicious Flower

- Udumbara Flower

- Return to Origin

- Celestial Cloud

- Elf Forest

- Gold Lotus

- Serene Lotus

- Pearl Elegance

- Radiance

- Metropolis Hermit

- The Nine

- Moon Goddess

- Tassel Elegance

- Chic Velvet Choker

- The Cloud

- Lotus Leaf

- Realm of Peace

- Four Season

-

Craftsmanship

-

Gemstones

- Pearl | Purity and Wisdom

- Jade | Stone of Heaven

- Turquoise | Protection and Healing

- Tridacna | Realm of Peace

- Lapis | Truth and Enlightenment

- Rose Quartz|Love, Healing, Compassion

- Amethyst | Clarity and Tranquility

- Amber | Vitality and Protection

- Carnelian | Courage and Vitality

- Coral | Protection and Prosperity

- Tourmaline | Energy and Balance

- Crystal | Healing and Clarity

-

Birthstone

-

Style

-

Price

-

- Jewelry Set

- Necklaces

- Earrings

- Bracelets

- Hair Jewelry

- Glasses Chains

- Rings

- Anklets

- Ornaments

- Login

-

English

8% off orders over $100, 15% off orders over $150, 20% off orders over $300.

Chinese Enamel and Cloisonné Jewelry: Painting with Glass

March 01, 2016 2 min read

Glass has long been in the Chinese jeweler’s toolkit, though for most of history, it was used as an imitation material for expensive or rare gemstones. If a noblewoman would wear imported beads of lapis lazuli, her maid might have to get by with beads of blue glass.

While it’s tempting to think of glass jewelry with the same disdain we reserve for knockoff handbags, it’s worth noting that a craftsperson’s imagination and attention to detail can propel even the humblest materials to great artistic heights.

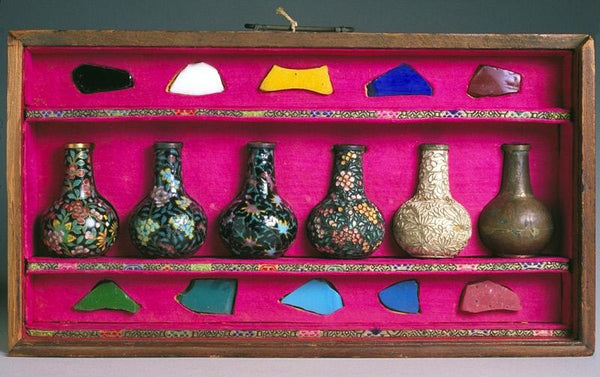

Enamelwork is a prime example of that. Enamelwork, known in China as “jingtailan” or “fa lang,” is the application of colored glass powder to metals.

A well known type of enamelwork called cloisonné involves creating areas using strips of metal attached to the main surface. These compartments are each filled with glass powder of varying hues.

Sometimes multiple colors are placed together in the same cell to create a gradient effect. The piece is then fired, melting the glass into smooth areas of color. Finally, any excess metal extruding from the surface is cut and sanded away.

Watch a jeweler demonstrate cloisonné technique in this short video:

Re- Re- Re-Introduction

If the look of cloisonné reminds you of a cathedral’s stained glass windows, that’s because the technique has roots in Europe. Europeans, in turn, inherited it from the Byzantine and Roman empires, which picked it up from the Egyptians. But as to when and how it came to China, accounts differ.

Some say China developed it in the Spring and Autumn period, the nearly 300 years of chaos that unraveled the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC). Others say it was as late as 1271, when Mongols incorporated China into its empire stretching across Asia and the Middle East, thus allowing Islamic arts—enamel among them—to take root in China proper.

Realistically, it was somewhere in between. From artifact evidence, enamel work didn’t seem to have reached China until the Tang dynasty (618–907), long after enamels were popular in the West. The Tang was a period of great wealth and intercontinental trade, and so the art of enamel flourished, adopting the grand and cosmopolitan style that characterized that time.

Sadly, few examples of Tang enamel exist today. Instead, the majority available to us are the most recent Ming and Qing dynasties. By the time of the Qing, enamel and cloisonné was enjoying a rather gusty second wind, aided by Emperor Kangxi, who is known to have been enamored of the work by French glass artist Bernard Perrot (1640–1709). Perrot accepted a residency at the Qing court and produced a variety of enamelware masterpieces, many of which were bestowed upon foreign emissaries in the emperor’s favor.

Eventually, enamel and cloisonné, having been sinicized, wound its way back to Europe, and people couldn’t get enough of all things “chinoiserie.”

This article is part of the Divine Land Gemstone Compendium, a weekly series by Yun Boutique exploring the gemstones of ancient China and their significance to Chinese culture. See the full series here. Subscribe to the email newsletter to receive future installments.

Produced and edited by Christine Lin. Researched by Ariel Tian.

Leave a comment

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …